eBriefs

Computer

Games - Interactive Movies - Players

- Stakeholders -

Local

Censorship - Overseas Censorship - Developer

Responses - Accusations

How are computer games censored in Australia?

How are computer games censored in Australia?

Although computer games have

been played in this country since at least the 1980s, it was only in the

1990s that people began to consider the idea of classifying these increasingly

popular and realistic products. In May of 1993, Labor Senator Margaret

Reynolds, horrified by the realistic computer game Night

Trap, began to actively campaign

for a system to regulate these products. By October, her influential

Senate

Select Committee on Community Standards Relevant to the Supply of Services

Utilising Electronic Technologies released a highly critical report

on computer games based largely on anecdotal evidence and conjecture -

the Report on Video and Computer Games

and Classification Issues - that firmly recommended their harsher

regulation than for film.

A further report by the Senate

Committee in 1994 - the Report on Overseas

Sourced Audiotex Services, Video and Computer Games, R-Rated Material on

Pay TV - reiterated many of its earlier findings on computer games.

Both sides of the House of Representatives praised the new Classification

(Publications, Films and Computer Games) Bill as rightly following

all the Senate Committee's recommendations. Newly developed computer

games classification guidelines banned almost all forms of sex and

nudity in computer games available in Australia.

The following year, the new

Classification Act came into force and allowed Federal classification decisions

to be rigorously enforced at the State level such as by Queensland's

Classification of Computer Games and Images (Interim) Act.

The first major, popular game from overseas, Phantasmagoria,

was Refused Classification and thus banned to all Australians. Similar

decisions that prevented all Australians from accessing popular computer

games from overseas were soon to follow.

All actions taken by Australian

governments to regulate the sale and distribution of computer games were

inspired by universal agreement with two key recommendations that arose

from the Senate Committee's 1993 Report:

Recommendation number six

on page vi stated:

Having regard to the

extra sensory intensity involved in the playing of interactive games and

the implications of long-term effects on users, the Committee recommends

that stricter criteria for classification than those applying to equivalent

film and video classifications be set by [classification] authorities...

Recommendation number four

on page v supported number six by proclaiming:

The Committee is concerned

that the level of technology involved with the use of ... computer games

means that many parents do not necessarily have the competency to ensure

adequate parental guidance. Therefore the Committee recommends that

material of an 'R' equivalent category be refused classification.

The Committee also recommends that if an 'X' equivalent classification

is considered it should not be adopted for ... computer games material...

In other words, it was heavily

implied that children are the only players of

computer games (or at least comprise the vast majority of players),

and that parents do not play them, and, in fact, have very low computer

competency. As a compounding factor to lead to severe regulation,

computer games were deemed to be of greater impact on users due to their

"extra-sensory intensity" in comparison to film.

Resulting

from these beliefs were the Office of Film

and Literature Classification's (OFLC) 1994 computer

games classification guidelines which remain in force today.

The OFLC is a Federal Government agency located within the Attorney General's

Department that is primarily responsible for classifying all films (including

videos) and computer games made available for sale or hire to the public

in Australia. Using official, periodically

reviewed guidelines, these products are assigned ratings according

to their suitability to certain age groups and many are additionally provided

with consumer advice giving a very brief summary of the reasons for the

rating.

Current ratings for computer

games (in order of level of restriction, least restrictive first) = G (all

ages), G 8+, M 15+, MA 15+, RC (Refused Classification). For films

= G, PG, M 15+, MA 15+, R 18+, X 18+ (video only), RC. Products refused

classification may not be sold or hired in Australia.

Aside from allowing for significantly

fewer ratings than for film, the computer games ratings most notably exclude

all non-medical instances of sex or nudity (real or simulated, whether

using animated figures or real human actors, and regardless of context

or plot requirements) from computer games made available in this country.

This is in stark contrast to the far more liberal attitude taken under

the film classification guidelines which allow for such material from as

low as the PG or M 15+ ratings.

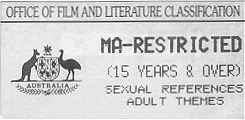

An example of an OFLC classification sticker for the highest legal

rating for computer games (MA 15+). Brief reasons for the rating

are provided in the form of associated consumer advice.

The OFLC operates from a relatively small, secluded building located

in an alleyway a couple of kilometres from Sydney's CBD. They occupy

the top two levels. Overly inquisitive visitors are not welcome on

level 6! Both levels are high security areas (e.g. photography is

banned and one can see security coded doors, small reception areas, and

very small reception desks).

Further

details of my visit to the censorsCurrent members (censors) of the OFLC's Classification Board

Information on the newly appointed OFLC Classification Board members